The Slowdown at Alang: An Unprecedented Crisis for India’s Biggest Shipbreaking Yard

Alang, Gujarat:

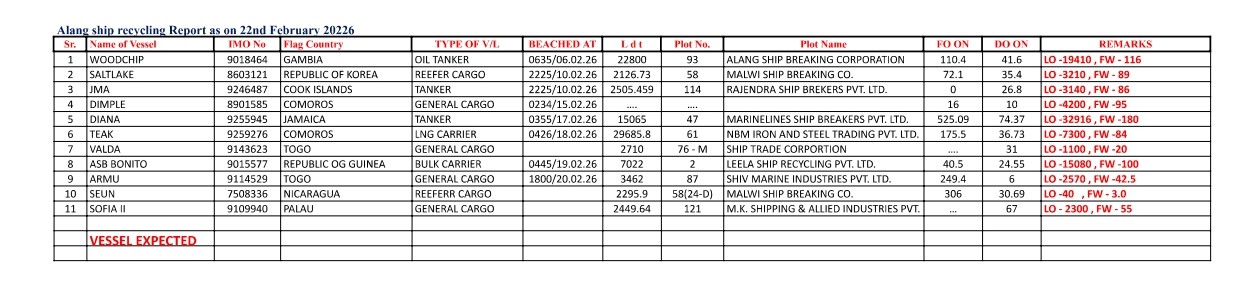

The Alang shipbreaking yard once hailed as the largest of its kind in the world, now faces an 18-year low in business. The number of ageing ships making their final voyage to be dismantled has drastically reduced, with over 80 per cent of the plots — individual lots where the recycling happens — standing empty. This downturn is causing alarm among those in the industry, including Mukesh Patel, chairman of Shree Ram Group, one of the largest shipbreaking companies in the region.

“Eighty per cent of Alang is dead,” Patel declares, his frustration evident. He reminisces about the bustling days of 2020, when his group dismantled India’s retired aircraft carrier, *Viraat*. Now, he says, only two of his six plots are in operation, and those too are on the verge of running out of work within a month. “My business is down by 70 per cent,” he laments.

Alang is located in Bhavnagar district on Gujarat’s coast and is known for its critical role in the global recycling of ships. But a sharp decline in business has left shipbreakers like Patel, as well as thousands of workers, in a precarious situation. Last financial year, the yard handled only 125 ships weighing a cumulative 9.4 lakh light displacement tonnage (LDT), a significant drop compared to its annual capacity of over 400 ships. The only comparable downturn occurred during the 2007-08 global financial crisis when 136 ships arrived at the yard.

As of August 2024, the picture remains bleak. Alang had handled just 2.99 lakh LDT of ships — a 16 per cent drop from the 3.5 lakh LDT in the previous year. Out of the yard’s 153 plots, only 20 are actively being used, and the number of workers, mostly migrants, has plummeted from a peak of 40,000-60,000 to a mere 3,500.

A Crisis Deepens: Declining Demand and Faulty Policies

The sharp decline in the number of ships arriving at Alang can be traced to multiple factors, including a global sluggishness in the shipping and shipbreaking sectors. But according to Patel and other shipbreakers, a significant part of the blame falls on the Gujarat Maritime Board’s (GMB) policy decisions.

Patel criticizes the GMB’s limitations on plot sizes, arguing that these restrictions make it difficult to attract large, lucrative ships from defence agencies in the US and Europe. “Bigger plots and more flexible policies are essential,” he says. “The political leaders focus on portraying Alang as a ‘green’ shipyard but are ignoring the need to attract more business.”

The GMB’s emphasis on environmental sustainability, though lauded by some, has not yielded tangible results for shipbreaking companies. Shipbreakers at Alang have made significant investments in green practices, such as upgrading their facilities to meet international environmental standards, yet the efforts have done little to reverse the economic downturn.

Steel Prices Compound the Crisis

Beyond policy issues, the demand for ship-recycled steel — a key driver of the shipbreaking business — has plummeted. Dubai-based Global Marketing Systems (GMS) Inc., the world’s largest buyer of ships for recycling, attributes much of the decline to the falling demand for locally produced steel.

“The ship recycling business is closely tied to the demand for scrap steel, which is produced when ships are dismantled,” says Nayeem Noor, Business Development Head at GMS. “But in recent years, India has seen an influx of cheaper, imported steel and alternative materials. As a result, the demand for scrap steel from recycled ships has diminished.”

This reduction in demand has struck a devastating blow to Alang, which depends heavily on the sale of scrap steel. Historically, when the supply of ships for recycling declined, the steady demand for steel helped stabilize the market. This time, however, both the supply of ships and the demand for steel have dropped simultaneously, creating what Noor calls “a perfect storm.”

According to shipbreakers, Indian steel producers have struggled to compete with cheaper imports, leading to a surplus of locally produced steel. With limited outlets for selling scrap, shipbreakers are finding it increasingly difficult to justify the cost of purchasing old ships for recycling.

Hopes for Recovery

Despite the ongoing crisis, the GMB remains optimistic about the long-term prospects of Alang. Rajkumar Beniwal, Vice-Chairman and CEO of the GMB, believes the decline is only temporary, a consequence of global economic factors. “Since the Covid pandemic, the number of ships being sent for recycling has been on the decline as ship owners prefer to rehabilitate old ships and extend their usage,” he explains.

However, Beniwal sees hope on the horizon. In the next three to four years, he predicts a sharp increase in the number of ships coming to Alang as older vessels become less viable for refurbishment. “We are also in discussions with the European Union (EU) to attract more ships from Europe to be recycled at Alang,” he says.

Currently, the EU does not send ships to Alang due to environmental concerns, but Beniwal is optimistic that upcoming surveys and assessments by EU officials could change that. The GMB is also working on initiatives to double Alang’s shipbreaking capacity, potentially increasing the yard’s annual LDT from 4.5 million to 9 million. This expansion would include the creation of 50 new shipbreaking plots, which could provide a much-needed boost to the industry.

Long Road Ahead

While GMB’s plans are promising, several obstacles need to be overcome for Alang to return to its former glory. One of the most pressing issues is the upgrade of infrastructure, which the GMB acknowledges is underway. “We are enhancing waste treatment facilities, health services, and worker accommodations at Alang,” says Beniwal. However, these upgrades will take time to complete, and with business already at a historic low, time is a luxury many shipbreakers feel they don’t have.

Additionally, the global economic environment remains uncertain, with many ship owners opting to extend the lives of their vessels through refurbishment rather than sending them for recycling. As a result, the pipeline of ships bound for Alang could remain thin for the foreseeable future.

A Bleak Future for Workers

The human toll of Alang’s downturn cannot be ignored. Thousands of migrant workers who once found steady employment at the yard have been forced to return to their home states, particularly Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Odisha. With only 3,500 workers remaining, many of whom are on the verge of losing their jobs, the future of Alang’s workforce hangs in the balance.

For the workers who remain, conditions have worsened. Fewer ships mean less work, and the wages they depend on are shrinking. Despite promises of improved worker facilities, those currently employed at the yard struggle with declining income, inadequate housing, and lack of proper health care.

One worker, who wished to remain anonymous, described the current situation as dire. “We came to Alang to find work, but now there is none. Every day, we hear about another plot closing down. We don’t know if we’ll be here next month.”

Conclusion: Alang at a Crossroads

The once-thriving Alang shipbreaking yard finds itself at a crossroads, grappling with challenges on multiple fronts. Declining ship arrivals, diminished demand for steel, and unfavourable policies have created an unprecedented crisis that threatens the future of the industry. While the GMB and industry insiders remain hopeful for a recovery, the path ahead is uncertain.

For Mukesh Patel and others in the industry, immediate action is needed. “We cannot wait for three or four years,” Patel stresses. “Alang needs a lifeline now, or it will be too late.”

As the yard fights to stay afloat, the fate of thousands of workers and the local economy hang in the balance. Whether Alang will rise once again to become a global leader in ship recycling, or sink into further decline, remains to be seen.

Author: shipping inbox

shipping and maritime related web portal