How Declining Steel Demand Impacts the Indian Ship Recycling Industry

The Indian ship recycling industry, a vital cog in the country’s industrial ecosystem, is facing unprecedented challenges as global steel demand continues to wane. Once a thriving sector that capitalized on the scrapping of end-of-life vessels to supply steel to domestic markets, the industry is now grappling with falling profits, job losses, and an uncertain future. With India being home to the world’s largest shipbreaking hub at Alang in Gujarat, the ripple effects of this decline are reverberating across coastal communities and the broader economy.

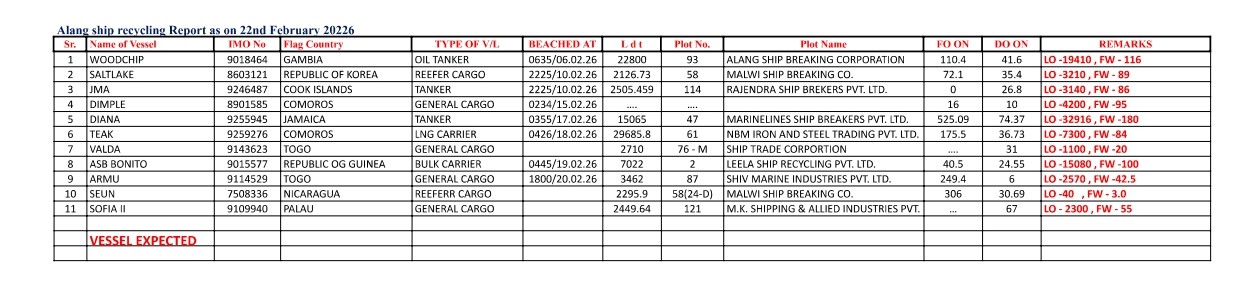

The ship recycling industry in India has long been a linchpin for the steel supply chain. Old ships, ranging from cargo carriers to oil tankers, are dismantled at yards like Alang, where workers extract steel and other materials for reuse. This recycled steel, often cheaper than newly produced metal, has traditionally fueled construction, manufacturing, and infrastructure projects across the country. At its peak, the Alang shipbreaking yard alone processed over 300 vessels annually, contributing significantly to India’s steel output and employing thousands of workers in labour-intensive roles.

However, the global steel market has undergone a seismic shift in recent years. A slowdown in construction and infrastructure development, particularly in key markets like China, has led to an oversupply of steel worldwide. Prices have plummeted as a result, with the benchmark price of hot-rolled steel dropping by nearly 20% over the past 18 months, according to industry reports. For Indian ship recyclers, this means that the steel salvaged from scrapped ships is no longer as lucrative as it once was. The profit margins, already thin due to high operational costs and regulatory compliance, are shrinking further.

“The demand for recycled steel has fallen sharply,” says Vikram Patel, a shipyard owner in Alang with over two decades of experience. “Earlier, we could sell steel at a premium because it was cost-effective for buyers. Now, with virgin steel prices so low, our customers are turning away. We’re left with ships that cost more to dismantle than the revenue they generate.”

The declining steel demand has also disrupted the supply side of the ship recycling equation. Shipowners, who once rushed to scrap aging vessels to capitalize on high steel prices, are now holding onto their fleets longer. With freight rates stabilizing and operational costs manageable, many are choosing to extend the life of their ships rather than send them to the breakers’ yards. Data from the Ship Recycling Association of India indicates that the number of vessels arriving at Alang dropped by 15% in 2024 compared to the previous year, a trend that industry experts expect to continue into 2025.

The economic fallout is stark. Alang, which employs over 30,000 workers directly and supports an additional 100,000 jobs in ancillary industries, is witnessing a slow exodus of labour. Workers who once earned steady wages cutting steel and salvaging parts are now facing layoffs or reduced hours. Local businesses, from food stalls to transportation services, are also feeling the pinch as the flow of money into the community dries up. “If this continues, Alang could turn into a ghost town,” warns Patel.

Environmental regulations add another layer of complexity. India has made strides in improving safety and sustainability standards at shipbreaking yards, aligning with international conventions like the Hong Kong Convention for Safe and Environmentally Sound Ship Recycling. While these measures have enhanced worker safety and reduced pollution, they have also driven up costs. Yards must now invest in better equipment, waste management systems, and compliance certifications—expenses that are harder to justify when revenues are dwindling.

Analysts suggest that the Indian ship recycling industry must adapt to survive. Some propose diversifying into other materials, such as copper and aluminium, which are also salvaged from ships and may fetch better prices in niche markets. Others advocate for government intervention, such as subsidies or tax breaks, to keep the industry afloat during this downturn. The Indian government has yet to signal any concrete plans, though discussions are reportedly underway in New Delhi.

For now, the future of India’s ship recycling industry hangs in the balance. As global steel demand shows little sign of rebounding, the once-bustling yards of Alang face a stark reality: evolve or fade away. The stakes are high—not just for the workers and businesses tied to the trade, but for India’s broader ambition to remain a leader in sustainable industrial practices. Without swift action, this vital sector risks being dismantled, piece by piece, much like the ships it once thrived on.

Author: shipping inbox

shipping and maritime related web portal