Bangladesh Shipbreaking Industry Faces Historic Decline Amid Global Disruptions

Bangladesh’s shipbreaking industry, long regarded as the global leader in ship recycling, experienced an unprecedented downturn in 2024. With global ship demolition reaching record low levels, only 144 ships, equivalent to 968,000 gross tons (GT), were sent to South Asia for recycling last year. This marks Bangladesh’s lowest level of scrap ship imports since 2005, a sharp contrast to its annual average of over two million GT.

Declining Numbers and Economic Impact

Bangladesh’s shipbreaking industry, centred in Chattogram, has traditionally dominated global ship recycling, dismantling nearly half of the world’s obsolete vessels. However, 2024’s figures underscore a dramatic shift. The industry peaked in 2021, with a record-breaking 280 ships (2.73 million GT) processed. By 2022, the volume had halved to 1.14 million GT, signalling the start of a worrying trend. The decline worsened in 2024, raising concerns about the sector’s sustainability.

“The numbers speak for themselves,” said Anam Chowdhury, President of the Bangladesh Marine Officers Association (BMOA). “This level of decline is not just a cyclical issue but a structural one, and it’s affecting thousands of workers who depend on this industry for their livelihoods.”

Global Disruptions Amplify Challenges

Multiple global factors contributed to the steep decline in shipbreaking activity. The Russia-Ukraine war, which began in 2022, disrupted global shipping routes and supply chains, leading to a drop in ship recycling volumes. This disruption was compounded in 2024 by the Red Sea crisis, which created an urgent demand for additional shipping capacity, including older vessels previously earmarked for demolition.

Adding to the challenges, demolition prices plummeted throughout 2024. In the first quarter, prices stood at $600 per Light Displacement Tonnage (LDT), but by December, they had dropped to $450/LDT, according to GMS, a leading cash buyer of demolition ships. The sharp decline in prices rendered shipbreaking less financially viable, forcing some Bangladeshi yards to temporarily shut down operations.

“When prices fall this low, it’s hard for yards to maintain profitability,” said a senior industry analyst. “This situation has left many yards in a state of limbo, particularly smaller operations that lack the resources to weather such downturns.”

Competition from India and Environmental Standards

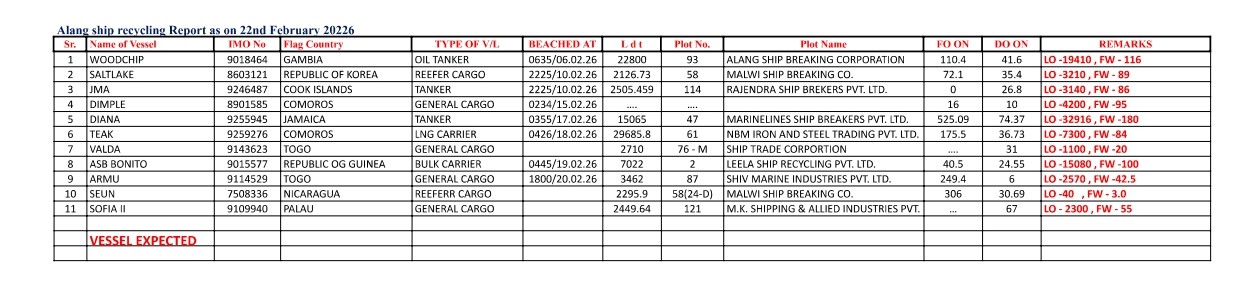

While Bangladesh struggles, its regional rival India is making significant strides in the shipbreaking sector. With over $100 million in funding from international donors, India has developed 120 green yards along the coast of Alang in Gujarat, adhering to the standards of the Hong Kong International Convention (HKC) for the safe recycling of ships. The HKC, set to take effect on June 26, 2025, mandates environmentally sound and safe recycling practices.

In stark contrast, Bangladesh has developed only five green yards in the past decade. This lack of progress has raised concerns that the nation’s inability to meet HKC compliance could jeopardize its dominance in the global ship recycling market.

“India’s investments in green yards are a game-changer,” said Chowdhury. “Bangladesh risks losing its top position unless it rapidly upgrades its yards to meet international standards.”

According to data from India’s ratings firm Care Edge, Bangladesh accounted for 46% of the global gross tonnage dismantled in 2023, compared to India’s 33%. However, with India’s growing compliance and capacity, the balance of power in the global shipbreaking industry is poised to shift.

Future Prospects and the Path Ahead

Despite the current downturn, industry experts believe the market could see a recovery in 2025. The anticipated uptick is tied to an expected increase in the availability of end-of-life ships, driven by new regulations requiring older vessels to be retired from active service. However, the long-term sustainability of Bangladesh’s shipbreaking sector will depend on its ability to adapt to global environmental standards and enhance operational efficiency.

“This is a wake-up call for Bangladesh,” said a senior environmental consultant. “The HKC compliance is not just a regulatory requirement; it’s a necessity for staying competitive in a market that is increasingly valuing sustainability.”

International funding and technical support could play a crucial role in helping Bangladesh modernize its yards. However, a lack of coordinated efforts and slow implementation of reforms have hindered progress so far.

Human and Economic Stakes

The shipbreaking industry in Bangladesh is not just an economic sector; it is a lifeline for tens of thousands of workers. Chattogram’s shipbreaking yards employ around 40,000 people directly and support an additional 200,000 indirectly. The decline in activity has left many workers facing unemployment and economic hardship.

“For us, this is not just about numbers; it’s about survival,” said one worker from a Chattogram yard. “We need the government and industry leaders to take urgent action to revive this sector.”

Conclusion

As Bangladesh grapples with the sharpest decline in its shipbreaking industry’s history, the stakes have never been higher. Global disruptions, falling demolition prices, and increasing competition from India have exposed vulnerabilities in the sector. The upcoming implementation of the HKC offers both a challenge and an opportunity for Bangladesh to modernize its yards and secure its position as a leader in ship recycling. However, without swift and decisive action, the nation risks losing its long-held dominance in the industry, with profound economic and social consequences.

Author: shipping inbox

shipping and maritime related web portal