Swift Arrests Over ₹21-Cr Tank Collapse: Silence on ₹1000-Cr GMB’s Maritime Projects Raises Questions

While seven were jailed within 48 hours over a Surat water tank failure, corruption allegations flagged by a senior BJP MLA in major Gujarat Maritime Board projects remain untouched

Gandhinagar: The Gujarat government’s swift action following the collapse of a newly constructed overhead water tank near Surat has been widely projected as a strong message against corruption and negligence in public works. Within 48 hours of the incident, the Surat Rural Police arrested seven persons — including contractors, consultants and government engineers — in connection with the failure of a ₹21-crore project that had not yet been opened to the public.

However, the speed and decisiveness of this response have also reignited a far more uncomfortable debate in Gandhinagar: why has similar action not been taken in alleged corruption cases involving projects worth more than ₹1,000 crore under the Gujarat Maritime Board (GMB), despite written complaints from a senior ruling party MLA and former minister naming the officer allegedly responsible?

The contrast between the two sets of cases — one involving a village-level water supply project and the other involving some of Gujarat’s most strategically important maritime and port infrastructure — has raised serious questions about consistency, accountability and political will in the state’s ongoing fight against corruption.

The Surat tank collapsed, and immediate action was taken

On the evening of January 20, 2026, an overhead water tank collapsed in Tadkeshwar village in Surat district, injuring three labourers on the site. The tank, approximately 15 metres high and designed to store around nine lakh litres of water, had been filled as part of a routine test run. The structure had not yet been commissioned for public supply.

Initial findings pointed to glaring lapses in design, execution and supervision. Acting with unusual speed, the Surat Rural Police registered a case and arrested seven individuals on January 22. Those taken into custody include contractors associated with Jayanti Super Construction, Mehsana — a joint venture partner in the project — officials of project management consultancy firm Mars Planning Private Limited, Ahmedabad, and two government engineers: a site engineer and an executive engineer from the water supply department.

A tale of two responses

While the government’s prompt response in the Surat case has been welcomed by many as a necessary assertion of accountability, it has also drawn attention to what critics describe as selective enforcement.

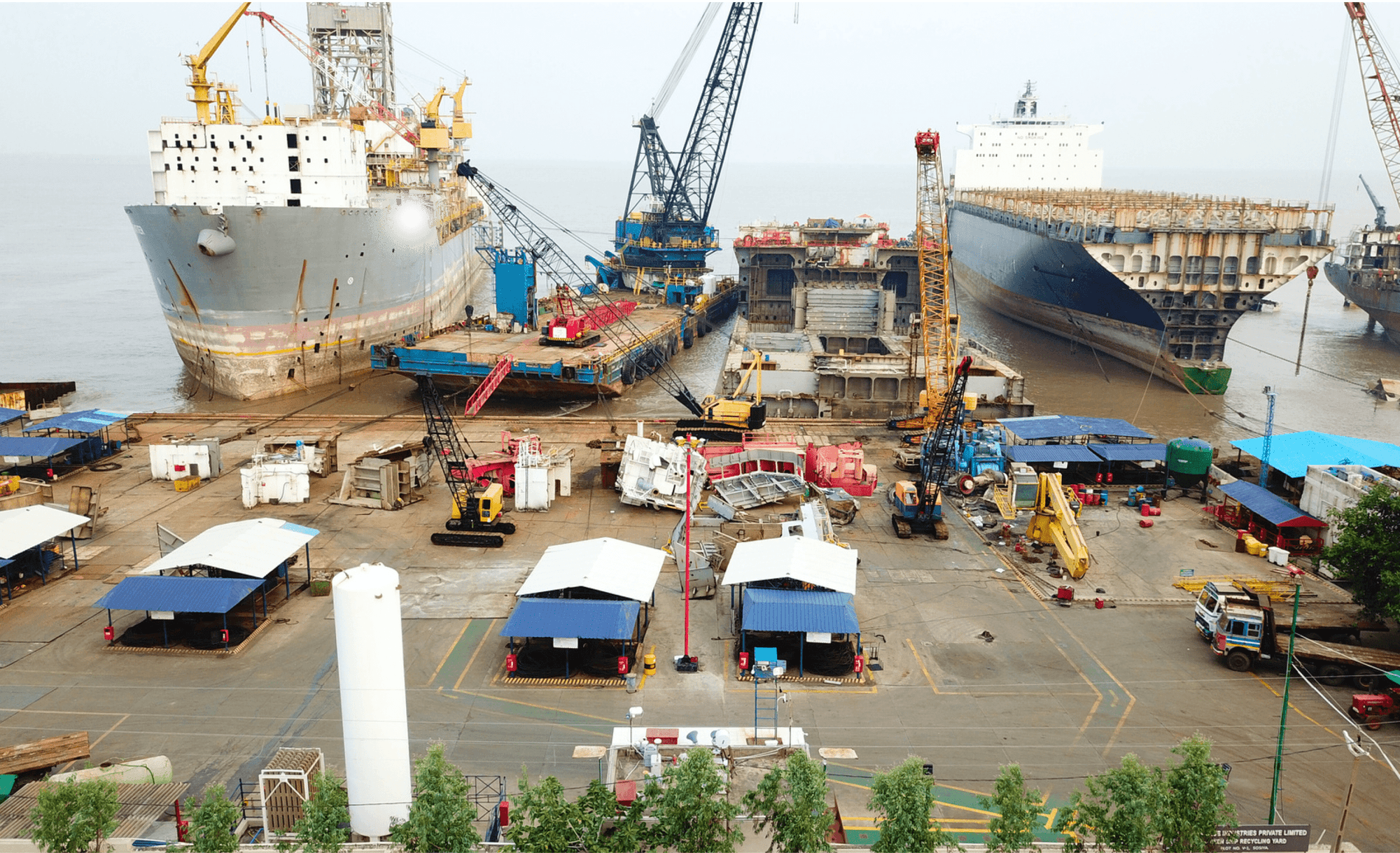

For years, allegations of corruption, technical lapses and mismanagement have dogged several high-value projects executed by the Gujarat Maritime Board — the powerful state body responsible for developing and managing non-major ports. According to critics, failures in at least four major GMB projects have resulted in losses running into hundreds of crores of rupees, with public funds effectively going down the drain.

Most significantly, a senior BJP MLA and former minister, Kishor Kanani (popularly known as Kumar Kanani), had written detailed letters to the Prime Minister, the Gujarat Chief Minister and top bureaucrats, explicitly naming a Chief Engineer of GMB, Mr Bhavesh Talaviya and seeking action over alleged corruption and gross negligence in these projects. Despite the seriousness of the allegations and the political stature of the complainant, no visible action has been taken so far.

Instead, according to sources, there is now active movement within the government and GMB to grant a post-retirement extension to the very officer whose name figures in the complaint — a development that has only deepened suspicions and fuelled outrage in bureaucratic and political circles alike.

The four GMB projects under the cloud

The projects cited in the allegations span Gujarat’s coastline and involve core maritime infrastructure critical to trade, security and regional connectivity.

Mangrol breakwater collapse:

One of the most glaring failures occurred at Mangrol, where a breakwater collapsed after sinking into the seabed. Preliminary assessments indicate that a proper geotechnical and hydrographic survey of the area was not conducted before construction. Instead of using large, heavy armour rocks as required for such structures, smaller stones and coral material were allegedly used. As a result, the breakwater failed to withstand marine forces and collapsed. The department is reportedly “investigating”, but no accountability has been fixed so far.

Vessel Traffic System (VTS) project:

In another case, the VTS project — meant to enhance maritime safety and monitoring along Gujarat’s busy coastline — was allegedly delayed deliberately for five to six years by postponing appraisal meetings. According to the complaint, this delay benefited certain private interests and caused cost escalations and operational setbacks. The matter is currently under mediation, but critics argue that mediation cannot substitute for criminal or departmental action if corruption is involved.

Ghogha–Dahej Ro-Ro ferry project:

Perhaps the most high-profile failure has been the Ghogha–Dahej Ro-Pax ferry service, once projected as a flagship connectivity initiative that would cut travel time between Saurashtra and South Gujarat. The project collapsed after repeated suspensions, with vessels frequently running aground. Deep-rooted corruption in dredging operations is alleged to have led to inadequate channel depth, making regular operations impossible. This case too is reportedly in mediation, even as the infrastructure lies largely idle.

Porbandar Navy berth:

At Porbandar, a berth constructed for both Indian Navy and commercial use has turned into a case study in flawed planning. The construction work, handed over to GMB, allegedly proceeded without a comprehensive study. The berth angle was changed by 15 degrees, with disastrous consequences. Today, only one vessel — either a cement ship or a Navy ship — can dock at a time. The resulting loss of berth rental revenue and operational flexibility has caused substantial financial loss and has also raised concerns about strategic preparedness.

SPV decision and deeper questions

Against this backdrop, the Gujarat government’s recent decision to grant in-principle approval for the formation of a special purpose vehicle (SPV) to develop, operate and maintain GMB-owned ports has triggered a wider debate.

Officially, the SPV is intended to accelerate redevelopment, bring in professional management and address long-standing maintenance bottlenecks at non-major ports. Unofficially, many see it as an admission that GMB, despite having a large technical workforce and decades of experience, has failed to deliver.

If GMB already has engineers, planners and an established institutional framework, critics ask, why was such a drastic structural intervention needed? More importantly, who is accountable for the years of neglect, failed projects and alleged corruption that necessitated this step?

Senior officials privately concede that the decision to create an SPV was forced by the dilapidated condition of several ports and mounting complaints from users, industries and coastal communities. Yet, there is little clarity on whether the move will be accompanied by a thorough audit of past decisions and individual accountability.

Political silence and internal discomfort

The lack of action on the GMB allegations has caused visible discomfort within the ruling party itself. The fact that a senior BJP MLA has gone public with complaints, writing to the highest offices in the country, suggests that concerns are not limited to opposition benches.

Sources say there is growing resentment among legislators who fear that selective action erodes the government’s credibility on corruption. “If arrests can be made within days for a ₹21-crore village project, why is there silence on ₹1,000-crore-plus maritime projects?” asked a senior party functionary on condition of anonymity.

A test case for governance

The Surat tank collapse case has, in many ways, become a test case for the Gujarat government’s governance narrative. Swift arrests have shown that the state machinery can act decisively when it chooses to. The question now is whether that resolve will extend to more complex, politically sensitive cases involving senior officials and strategic sectors.

Public finance experts warn that failure to act uniformly undermines deterrence. “Corruption is not just about the amount involved; it is about the principle of accountability,” said a retired auditor. “When large projects fail without consequences, it sends a message that scale provides immunity.”

What lies ahead

With the government now projecting itself as being active in the fight against corruption, expectations are rising that the complaint lodged by MLA Kishor Kanani will finally be acted upon. A credible probe into the four GMB projects, fixation of responsibility and transparent disclosure of findings would go a long way in restoring confidence.

As Gujarat embarks on structural reforms like the SPV for ports, the larger question remains unresolved: will institutional changes be accompanied by individual accountability, or will past failures simply be buried under new frameworks?

The answer will determine whether the Surat arrests mark the beginning of a consistent anti-corruption drive — or remain an isolated instance driven by political compulsion rather than principle.

Author: shipping inbox

shipping and maritime related web portal