Reconsider 5% Limit on Redeeming Ship Recycling Credit Notes and Introduce Tiered Caps: Dr Anil Sharma of GMS Inc

In an interaction with ET Infra, Dr. Anil Sharma, founder and CEO of GMS Inc, hailed India’s newly announced credit-note incentive for ship recycling as a “visionary step” that could significantly strengthen the country’s green dismantling ecosystem. However, he cautioned that the framework being drafted by the Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways carries structural limitations—most notably the 5% cap on redeeming credit notes against the cost of a newbuild—which, he said, risks locking up much of the scheme’s intended economic value and preventing it from achieving its full potential.

India’s ambitious plans to reshape its maritime industrial landscape have gathered fresh momentum with the government drafting guidelines for the Ship Recycling Credit Note Scheme. This initiative seeks to interlink the country’s dominant ship recycling sector with its still-nascent shipbuilding ambitions. The scheme is being watched closely by industry stakeholders worldwide, but perhaps no voice carries more weight in this conversation than that of Dr Anil Sharma, Indian-born founder and chief executive of GMS Inc, the world’s largest cash buyer of ships for recycling.

With a track record unmatched in global maritime circles—nearly 5,000 vessels delivered to recycling destinations over three decades, and even its own newbuilding experience with Ultramax vessels—GMS is uniquely positioned at the intersection of recycling, ship ownership, and shipbuilding. Speaking to ET Infra, Dr Sharma praised India for taking what he called a “visionary step” in linking recycling with newbuilding. But he also urged policymakers to refine the implementation framework to ensure that the scheme achieves its intended impact.

“India has taken a bold and visionary step,” he said, “but unless certain structural limitations are addressed—particularly the 5% redemption cap, indivisibility of credit notes, and a too-short validity period—the scheme may not reach its full potential.”

What follows is an in-depth look at his analysis, recommendations, and the larger implications for India’s maritime future.

A Visionary Policy at a Critical Moment

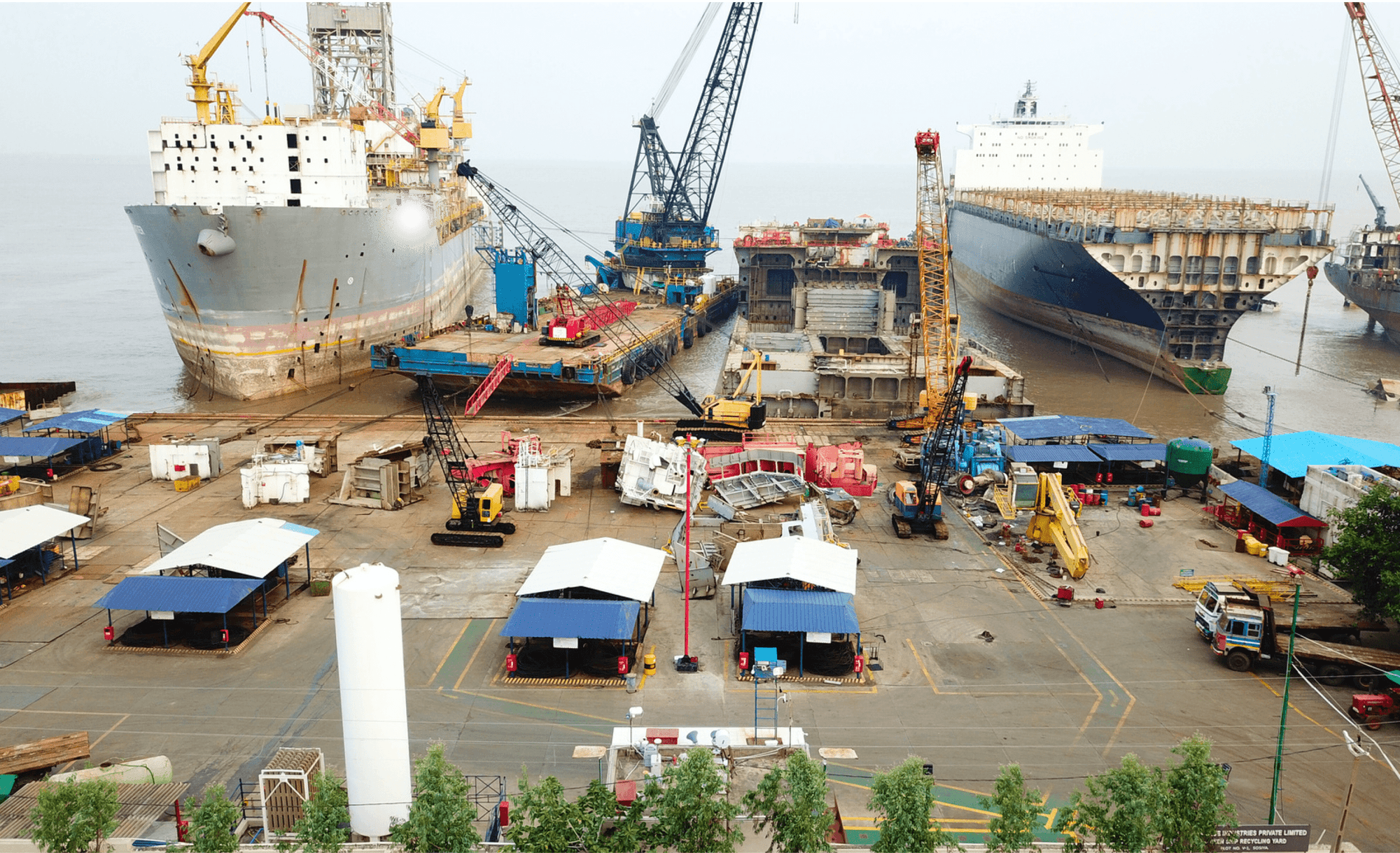

India today accounts for over 30% of global ship recycling activity, with the Alang–Sosiya belt in Gujarat standing as the world’s most developed green recycling cluster. Yet, in recent years, India’s dominance has come under pressure. Bangladesh’s aggressive pricing, Turkey’s growing capacity for EU-flag tonnage, Europe’s increasing insistence on recycling EU-flag ships in EU-approved yards, and a cautious re-emergence of Pakistan all pose competitive challenges.

Simultaneously, India’s shipbuilding footprint remains small when compared to global leaders—China, South Korea, and Japan—which together dominate over 85% of worldwide shipbuilding orders.

In this context, the government’s Ship Recycling Credit Note Scheme—designed for recycling yards to issue credit notes to cash buyers or shipowners, who can redeem them against the cost of building new ships in India—is aimed at catalysing two outcomes at once:

-

Strengthening India’s position as the preferred global recycling hub, and

-

Kickstarting a long-awaited surge in shipbuilding orders at Indian yards.

Dr Sharma believes the policy is exactly what India needs to leapfrog into a higher category of maritime capability.

“Countries that lead in global shipbuilding today did not reach that status naturally. They got there because their governments stepped in at the right moment,” he said.

“India is doing the right thing—but execution must be flexible, realistic, and globally competitive.”

Learning From Global Precedents

The case for interventionist maritime industrial policy is well supported by global history. Dr Sharma cited several examples:

China’s Subsidy Programme

In the early 2010s, China launched a recycling-linked subsidy programme to support domestic newbuilding. Shipowners recycling old ships at Chinese yards received financial incentives to place newbuilding orders in China. The results were transformative:

-

A dramatic surge in shipbuilding orders

-

The rapid expansion of domestic shipyards

-

China becoming the world’s largest shipbuilding nation

Japan & South Korea

Both countries have for decades used a combination of export-credit agencies, interest-rate subsidies, long-term industrial policies, and technology support to build world-class shipbuilding clusters.

United States

Washington is now preparing major funding packages to revive American shipyards under its “Build American Ships” initiative—proof that even the most advanced economies rely on state support when rebuilding strategic industries.

Europe

Several European nations used shipbuilding subsidies extensively during their industrialisation cycles. Many still do, although under restructured frameworks that comply with EU regulations.

Given this global backdrop, Dr Sharma’s message is clear:

“Subsidies are not distortions—they are essential for countries that are still developing shipbuilding ecosystems. India must use the same playbook that global leaders used when they were in the early stages.”

Why the Credit Note Scheme Matters for India

According to GMS, the proposed scheme solves three structural challenges simultaneously.

1. It Repositions India as the “Destination of Choice”

Cash buyers and shipowners weigh multiple factors when selecting a recycling destination—price, compliance, regulations, logistics, and incentives. With credit notes providing value for future newbuildings, India immediately becomes more attractive.

“Cash buyers like us will naturally send more ships to India to earn credit notes. That is guaranteed. The incentive alignment is powerful.”

2. It Creates a Circular Maritime Economy

Recycling generates value that directly feeds into newbuilding. China’s model provides clear proof: once shipowners realised they gained significant advantages by recycling and building in the same country, the domestic maritime loop began to reinforce itself.

3. GMS’ Unique Position Helps Scale the Scheme

GMS’ unmatched footprint offers India an execution partner like no other:

-

Decades-long relationships with shipowners

-

A dominant share of global recycling deliveries

-

Experience with building its own Ultramax vessels

“With our blend of recycling scale and shipbuilding experience, we are well placed to support India in implementing this scheme globally,” Sharma said.

Safeguards and Misuse: A Misplaced Concern

Some policymakers have expressed concern about the scheme being potentially misused, particularly since few cash buyers maintain ship-owning arms. Dr Sharma dismissed these fears as unnecessary.

Stringent Oversight Already Exists

Recycling in India is monitored by:

-

Customs

-

Gujarat Maritime Board

-

Directorate General of Shipping

-

International classification societies

-

Global shipbrokers and auditors

-

Media scrutiny

Every step is documented, audited, and traceable.

“Reputable, audited cash buyers are already legally responsible for recycling transactions. The chance of misuse is negligible.”

The real challenge, he said, is not misuse—but rigid structural limits that undermine commercial practicality.

The Structural Flaws Holding Back the Scheme

Dr Sharma identified three major issues that could significantly reduce the scheme’s effectiveness.

1. The 5% Redemption Cap: Too Low to Be Effective

Under the current draft, a recycled ship may generate credits worth up to 40% of its scrap value. But a shipowner or cash buyer can redeem only 5% of the cost of a newbuilding.

Example:

-

Scrap value of a ship: ₹100 crore

-

Credit generated (40%): ₹40 crore

-

But allowable redemption on newbuild: only 5% of newbuilding cost

If the new ship costs ₹500 crore, the maximum redeemable value is just ₹25 crore, even if the credit note holds more value.

Dr Sharma calls this economic misalignment “counterproductive.”

“It traps the credit notes’ economic value. The limit must be reconsidered.”

2. Indivisible Credit Notes: A Roadblock for Real-World Transactions

Currently, credit notes cannot be partially redeemed. Whether the value exceeds the cap or not, shipowners must use the entire note in one shot—otherwise the balance is forfeited.

Dr Sharma says this is commercially impractical:

-

Shipowners often build multiple smaller ships

-

Newbuilding decisions are staggered over cycles

-

Investors prefer flexible credit utilisation

“Indivisibility restricts deal-making, reduces flexibility, and makes the scheme less attractive to global players.”

3. Three-Year Validity: Too Short for Global Shipowners

Shipowners operate on long investment timelines. It often takes:

-

1–2 years to evaluate newbuilding

-

6–18 months for internal approvals

-

2–3 years to align with market cycles

-

6–12 months for final negotiations

Many shipowners operate on 4–6 year cycles between recycling and newbuilding decisions.

“Three years is simply not enough. Many credit notes will expire unused.”

GMS’ Prescriptions: Flexible, Realistic, Impact-Focused

To address these issues, Dr Sharma has recommended a set of modifications he believes will unlock the scheme’s full potential.

1. Reconsider the 5% Cap

For initial orders, he suggests increasing the cap to 10%:

-

Early adopters provide momentum

-

Higher usage demonstrates the scheme’s value

-

Encourages international shipowners to place orders in India

2. Introduce Tiered Caps for Strategic Ship Types

For certain vessel categories—where India seeks technological advancement—the cap should be higher, up to 15%:

-

Green or low-emission ships

-

LNG or LPG carriers

-

Offshore vessels

-

Technologically complex ships

These categories align with India’s modernisation goals and environmental commitments.

3. Allow Partial Utilisation and Splitting Across Multiple Newbuildings

Credit note flexibility will:

-

Increase commercial attractiveness

-

Enable broader participation by diverse shipowners

-

Prevent loss of credit value due to indivisibility

-

Encourage multiple orders instead of just one

4. Extend the Validity Period

GMS proposes:

-

Minimum validity: 5 years

-

Optional extension: up to 7 years

This aligns with the reality of global newbuilding cycles and the pace of capital allocation.

Should Cash Buyers Be Treated as Owners? Dr Sharma Says “Absolutely, Yes.”

One policy question under consideration is whether cash buyers or original shipowners should be treated as the “owners” for the purpose of credit note issuance.

Dr Sharma’s stance is unequivocal.

“Cash buyers must be recognised as the legal owners. This is supported by global maritime practice, contractual law, and the IMO itself.”

He cites detailed IMO legal studies conducted during the drafting of the Hong Kong Convention (HKC), which concluded that:

-

When a ship is sold for recycling, the cash buyer becomes the actual owner.

-

Ownership is not symbolic—it includes full financial, legal, environmental, and commercial responsibility.

-

The original fleet owner has no liability or involvement after sale.

Cash buyers pay:

-

Full vessel consideration

-

All taxes and duties

-

All port and statutory charges

-

All recycling-related liabilities under Indian law

Therefore, he argues, treating the original fleet owner as the “owner” for another 2–3 years is legally untenable and commercially unworkable.

“Recognising cash buyers as owners is essential for clarity, efficiency, and compliance with international norms.”

A Pivotal Moment for Indian Maritime Ambition

India’s maritime aspirations are at a crossroads. The country already leads the world in safe and green ship recycling capacity. With the right policies, it could become a significant player in global shipbuilding—especially in specialised segments like offshore vessels, coastal tonnage, defence auxiliaries, and green-fuel capable ships.

The Ship Recycling Credit Note Scheme offers a strategic opportunity to bridge India’s strengths with its ambitions.

Yet success depends on flexibility, practical design, and alignment with global commercial dynamics.

Dr Sharma summed it up succinctly:

“India has taken a visionary step. But for the scheme to deliver its true potential, the framework must be commercially realistic. A flexible, tiered, and investor-friendly model will attract more ships to India for recycling—and more shipbuilding orders to Indian yards. This is the way to transform India’s maritime future.”

With nearly 5,000 vessels already handled and the global influence of the world’s largest cash buyer behind the idea, India’s policymakers may have found in Dr Sharma not just a critic, but a strategic partner in shaping a new era for the Indian maritime industry.

Author: shipping inbox

shipping and maritime related web portal