Green Steelmaking and the Complex Legacy of Ship Recycling

As the world pivots toward sustainable industrial practices, steelmaking—a sector responsible for 8% of global carbon dioxide emissions—finds itself at the heart of the conversation. At the recently concluded COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, the spotlight was firmly on green steel production as a key component of industrial decarbonization. This transition to greener practices involves utilizing electric arc furnaces (EAFs) powered by renewable energy and shifting away from coal-fired induction gas furnaces. Another promising approach includes incorporating ferrous scrap into the raw material chain, significantly reducing carbon emissions.

The Role of Scrap-Based Electric Arc Furnaces

Scrap-based electric arc furnaces have emerged as a cornerstone of green steel production. These furnaces can reduce carbon dioxide emissions by up to 75% compared to traditional blast furnaces. They rely heavily on recycled steel, primarily sourced from dismantled automobiles, machinery, and ships. This approach is not only environmentally friendly but also cost-effective, making it particularly appealing to developing and emerging economies where investments in hydrogen- or natural gas-based reduction technologies remain challenging.

The green steel revolution offers a dual benefit—lower emissions and economic efficiency. However, it also opens up debates about the environmental and ethical implications of scrap sourcing, particularly from the ship recycling industry.

Ship Recycling: An Environmental Paradox

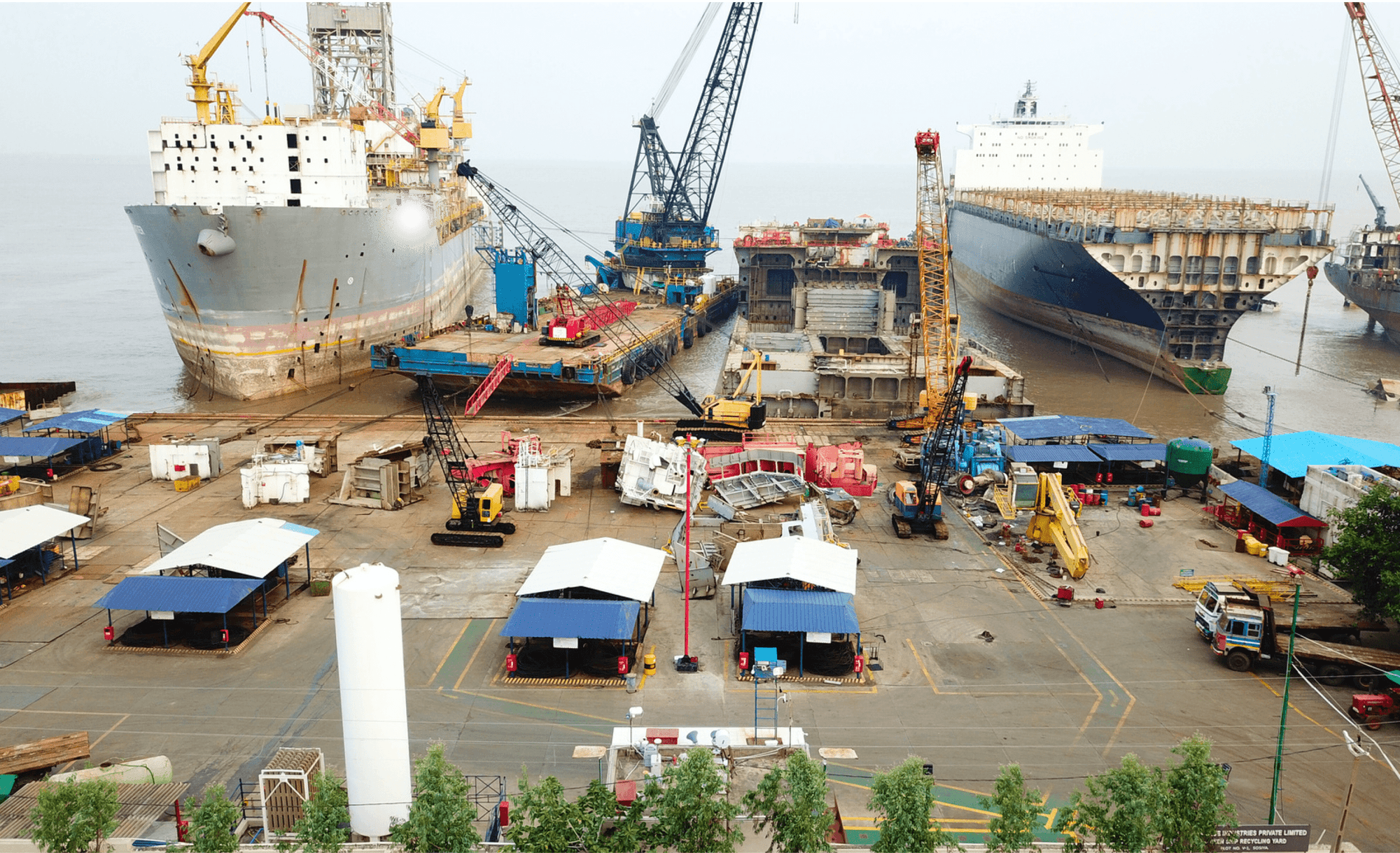

Ship recycling is a major source of ferrous scrap, with South Asia—particularly India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan—dominating the global market. Alang, located in Bhavnagar, Gujarat, is the world’s largest shipbreaking yard, capable of dismantling up to 450 ships annually. Together with facilities in Chattogram, Bangladesh, and Gadani, Pakistan, these yards account for over 90% of global ship recycling.

However, shipbreaking in South Asia remains one of the most polluting industries. The practice, known as “beaching,” involves dragging ships onto tidal flats for dismantling. This method, while cost-effective, often results in severe environmental degradation, including soil and water contamination from hazardous materials like asbestos, heavy metals, and oil residues. Moreover, the industry has a dismal record on worker safety, with frequent accidents and exposure to toxic substances claiming many lives annually.

The Flag of Convenience: Evading Responsibility

A significant issue in the ship recycling industry is the widespread use of the “Flag of Convenience” (FOC) system. Under this arrangement, shipowners—primarily from Western nations—register their vessels in countries with lax regulations, such as Panama or the Marshall Islands. This practice allows owners to evade stringent environmental and labour laws in their home countries.

Once these ships reach the end of their operational life, they are sold to cash buyers who operate in South Asia. These buyers, in turn, sell the vessels to recycling yards like those in Alang. The original owners are absolved of any responsibility for the environmental and human costs of dismantling.

Regulatory Frameworks and Their Limitations

In response to the environmental and safety concerns, international regulations have been introduced. The Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships (HKC), adopted in 2009, aims to ensure that shipbreaking is conducted in a manner that safeguards human health and the environment. However, the convention allows beaching under certain conditions, provided the yards adhere to safety and hazardous material management protocols.

India has ratified the HKC, and about half of Alang’s yards are now certified as compliant by international agencies such as Lloyd’s Register. The convention is set to come into force in June 2025, but critics argue that it falls short of addressing the root environmental issues associated with beaching.

The European Union has also implemented stricter regulations under its Ship Recycling Regulation (EU SRR), which came into effect in 2018. It mandates that EU-flagged ships can only be recycled at approved facilities that meet stringent environmental and safety standards. However, this regulation applies exclusively to EU-flagged vessels, leaving a significant portion of the global fleet outside its ambit.

The Push for Green Steel and the Recycling Conundrum

At COP29, several Western nations advocated for the increased use of recycled ferrous scrap from shipbreaking as a resource for green steel production in South Asia. The argument is that the abundant supply of scrap from dismantled ships could provide a sustainable raw material base for EAFs in countries like India.

However, this push raises critical questions. While the use of scrap undoubtedly reduces emissions in steel production, it also perpetuates the environmentally harmful and hazardous shipbreaking practices prevalent in South Asia. The HKC, even when fully implemented, does not prohibit beaching—a practice inherently incompatible with true environmental sustainability.

Charting a Sustainable Path Forward

For India and other South Asian nations, the path to truly sustainable green steel production lies in balancing economic opportunities with environmental stewardship. Here are a few considerations:

- Modernizing Ship Recycling Infrastructure: Transitioning from beaching to dry-dock dismantling could significantly reduce environmental harm. Dry docks allow for controlled dismantling, minimizing the risk of soil and water contamination. However, this transition requires substantial investment and international support.

- Enhanced Regulation and Enforcement: Strengthening local regulatory frameworks and enforcing strict compliance with environmental and labor standards can mitigate the adverse impacts of shipbreaking. This includes comprehensive monitoring and accountability mechanisms.

- Alternative Scrap Sources: Expanding the scope of scrap sourcing beyond ship recycling—such as increasing the recycling of automotive and industrial machinery—can diversify the raw material base for green steel production.

- International Responsibility and Collaboration: Shipowners from developed countries must take greater responsibility for the end-of-life management of their vessels. This includes ensuring that ships are dismantled in environmentally sound facilities, even if it comes at a higher cost.

- Investment in Hydrogen-Based Steelmaking: While costly, hydrogen-based direct reduction of iron (DRI) offers a long-term solution for zero-emission steel production. International partnerships and funding mechanisms could help developing nations adopt this technology.

Conclusion

The transition to green steel is a critical component of global climate action. While scrap-based electric arc furnaces offer a promising pathway, reliance on ship recycling as a primary scrap source raises significant environmental and ethical concerns. To achieve true sustainability, South Asia’s shipbreaking industry must undergo a comprehensive overhaul, supported by robust international collaboration and investment.

As the world gears up for a low-carbon future, the focus must be on solutions that align environmental, economic, and social goals—ensuring that the green revolution in steel does not come at the cost of vulnerable ecosystems and communities.

Author: shipping inbox

shipping and maritime related web portal